Human Elements: The Most Complex Variable in Operational Systems

- Umashree

- 4 days ago

- 11 min read

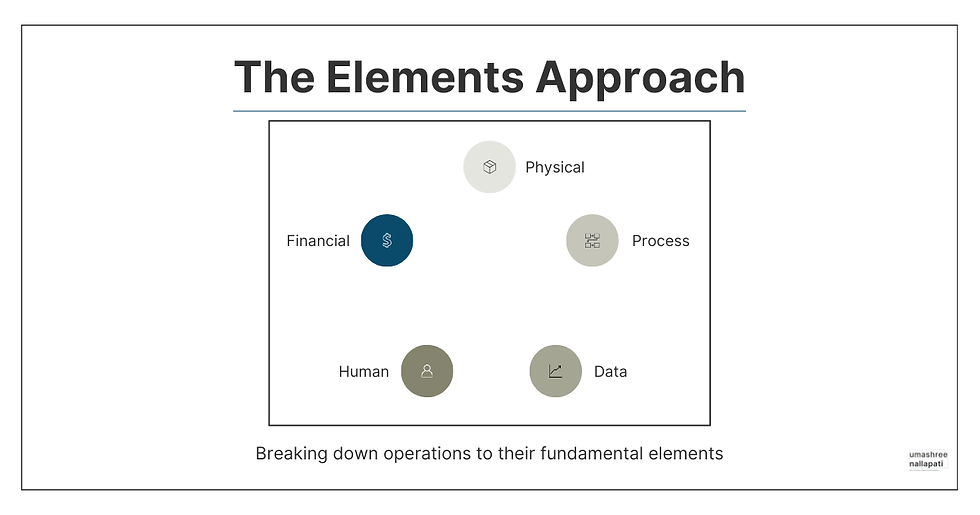

After two decades of analyzing distribution operations across the country, I've reached an inescapable conclusion: we've been looking at operational excellence all wrong. While most companies invest heavily in optimizing their physical assets, refining their processes, and implementing sophisticated data systems, they consistently undervalue the most powerful and complex variable in the equation: human elements.

This isn't just a philosophical observation—it's a pattern I've witnessed repeatedly in my work with distributors. The warehouse with state-of-the-art racking but disengaged staff. The ERP implementation that fails despite flawless technical execution. The perfectly designed process that somehow never quite delivers the expected results.

In each of these cases, the missing piece wasn't another equipment upgrade or a better algorithm—it was a failure to fully understand and design for the human elements in the system.

Understanding Human Elements in Distribution Operations

When we apply first principles thinking to operations, we must acknowledge that human elements operate by different rules than physical or process elements. While a conveyor belt behaves according to consistent physical principles and a database follows logical rules, human behavior emerges from a complex interplay of psychology, social dynamics, and individual differences.

A mid-sized plumbing distributor I worked with had implemented a new warehouse management system, complete with optimized pick paths and labor standards. On paper, it should have improved productivity by 30%. Six months later, they were seeing just 5% improvement, despite flawless technical implementation.

When we analyzed the situation through a human elements lens, the reasons became clear: the implementation had ignored critical psychological factors like autonomy, mastery, and purpose that drive human performance. The technology itself was sound—the human interface was the failure point.

The Four Core Human Elements in Operational Systems

Through applying first principles thinking to dozens of distribution operations, I've identified four core human elements that fundamentally shape operational outcomes:

Skills & Capabilities: The knowledge, abilities, and experience people bring to their roles

Behavioral Patterns: The habitual actions and reactions that determine how work actually gets done

Incentive Structures: The formal and informal rewards that shape behavior

Communication Patterns: How information and meaning flow between people

Much like physical or process elements, these human elements exist in your operation whether you've designed them intentionally or not. And just like their counterparts, they can either enable excellence or constrain performance.

The Myth of the Rational Operator: Human Psychology in Distribution Operations

Classical operational design assumes what I call the "rational operator"—a theoretical person who:

Makes decisions based solely on logic and available information

Follows processes exactly as designed

Maintains consistent performance regardless of context

Prioritizes organizational goals above personal preferences

Communicates with perfect clarity and precision

This mythical being makes operational design so much simpler. Unfortunately, they don't exist.

Real human operators:

Make decisions influenced by cognitive biases and emotional states

Adapt processes based on personal judgment and social norms

Vary in performance based on numerous contextual factors

Balance organizational and personal priorities dynamically

Communicate through imperfect language filtered through relationships

A building materials distributor I advised had implemented a sophisticated inventory optimization system. The algorithms were flawless, but their buyers consistently overrode the system's recommendations. When we investigated why, we discovered a fascinating human element: the buyers had been burned by stockouts in the past and had developed an emotional aversion to risk that no algorithm could override without addressing the underlying psychology.

Common Cognitive Biases Affecting Distribution Operations

Understanding how cognitive biases shape operational behavior can transform your approach to human elements. Here are three particularly consequential biases I've observed:

1. Availability Bias

People tend to overweight recent or emotionally salient events in their decision-making. In distribution operations, this often manifests as:

Overreacting to recent customer complaints

Perpetuating "emergency" ordering patterns after stockouts

Maintaining excessive safety stock for items that once had a problem

Avoiding certain suppliers based on isolated negative experiences

2. Status Quo Bias

Humans have a strong preference for the current state and resist change even when it's beneficial. In operations, this appears as:

Resistance to new processes regardless of their merit

Continuing inefficient practices because "that's how we've always done it"

Reverting to old methods when new ones require more initial effort

Adding workarounds rather than addressing root causes

3. Confirmation Bias

We naturally seek and interpret information that confirms our existing beliefs. Operationally, this leads to:

Selectively using data that supports current practices

Attributing failures to external factors while claiming credit for successes

Dismissing feedback that challenges established viewpoints

Implementing "solutions" that address symptoms rather than causes

By recognizing these biases, we can design systems that work with human psychology rather than against it.

Incentive Structures: The Invisible Forces That Shape Operational Behavior

Charlie Munger famously observed, "Show me the incentive and I will show you the outcome." In my experience with distribution operations, no principle holds more truth—yet few are more consistently overlooked.

Formal incentive systems in distribution typically focus on easily measurable outputs: lines picked per hour, orders processed per day, inventory turns achieved. But these explicit incentives often create unintended consequences by ignoring the complex behavioral systems they influence.

A foodservice distributor I worked with had implemented a productivity-based incentive for their warehouse staff. Pickers earned bonuses based on lines picked per hour, which seemed like a straightforward way to drive efficiency. Six months later, they were hitting productivity targets but experiencing rising error rates, increased product damage, and declining morale.

The incentive had worked perfectly—it had precisely incentivized the behavior it measured. Unfortunately, it had also created powerful disincentives for quality, care, and collaboration.

Designing Incentives That Align With System Goals

First principles thinking requires us to design incentive structures that work with human psychology rather than against it. Based on my experience with dozens of distribution operations, here are four key principles for effective incentive design:

1. Balance Countervailing Metrics

Never incentivize a single metric without considering what other behaviors might be sacrificed. Always pair efficiency metrics with quality metrics, utilization metrics with service metrics.

The foodservice distributor redesigned their incentive system to balance lines picked per hour with error rates and team performance. Within three months, they maintained productivity while reducing errors by 47%.

2. Align Individual and Organizational Success

Ensure that behavior that benefits the individual also benefits the organization. This alignment creates a reinforcing cycle rather than competing priorities.

A fastener distributor implemented a profit-sharing program that gave every employee visibility into how their daily actions affected company profitability. This created a natural alignment between individual and organizational incentives.

3. Consider Intrinsic Motivators

While financial incentives matter, research consistently shows that autonomy, mastery, and purpose are more powerful motivators for complex tasks. Design systems that enhance rather than undermine these intrinsic motivators.

An electrical distributor restructured their picking process to give teams greater autonomy in how they fulfilled orders. Despite removing financial incentives, productivity increased by 12% and error rates declined by 23%.

4. Account for Social Incentives

Humans are fundamentally social creatures. Recognition, status, and social connection often drive behavior more powerfully than formal incentives.

A building products distributor implemented a simple recognition program highlighting exceptional customer service. This zero-cost intervention improved customer satisfaction scores more than their previous financial incentive program.

Communication Patterns: The Unseen Element in Operational Excellence

Information flow is the lifeblood of any operation, yet the human elements of communication are frequently overlooked in operational design. When we examine communication through a first principles lens, we discover that it's not merely about transmitting data—it's about creating shared understanding.

A plumbing distributor I advised had implemented a sophisticated inventory management system, but branch managers consistently complained about poor replenishment performance. The technical system was functioning perfectly, but when we mapped the communication patterns, we discovered that the system's outputs weren't creating shared understanding—they were creating confusion and mistrust.

The Communication Element Framework

Through dozens of operational transformations, I've developed a framework for analyzing and optimizing communication patterns:

1. Information Pathways

Map how information moves through your organization:

Who communicates with whom?

Which pathways are formal vs. informal?

Where do bottlenecks or dead ends occur?

How does information cross departmental boundaries?

The plumbing distributor discovered that critical inventory information was flowing through six different people before reaching the branch manager, with each handoff introducing delay and distortion.

2. Communication Media

Examine the channels through which communication occurs:

Which topics are communicated through which media?

When are synchronous vs. asynchronous communications used?

How do digital and face-to-face communications integrate?

Which media create the most clarity vs. confusion?

An HVAC distributor realized that their buyer-planner conflicts stemmed from an overreliance on email for complex coordination that required richer interaction.

3. Language and Meaning

Analyze the actual content of communications:

Do key terms have consistent meaning across departments?

Where do specialized vocabularies create barriers?

How are ambiguities and uncertainties communicated?

What assumptions are embedded in the language used?

A lumber distributor discovered that sales and operations used the term "availability" differently, creating consistent miscommunication about service levels.

4. Feedback Loops

Identify how communication creates action and learning:

How do people know their communication was understood?

What mechanisms exist for clarification and correction?

How are communication failures identified and addressed?

What feedback exists about communication effectiveness?

The plumbing distributor implemented a simple confirmation protocol for inventory communications, reducing misunderstandings by over 70%.

The Human Element Analysis Framework

If you're ready to improve the human elements in your operation, here's a structured approach I've used successfully with dozens of distributors:

1. Skills and Capabilities Analysis

Start by mapping the actual vs. needed skills across your operation:

Where do current capabilities fall short of requirements?

How are skills currently developed and maintained?

Which capabilities create strategic advantage vs. basic function?

When a hardware distributor applied this analysis, they discovered their most significant performance constraint wasn't warehouse layout or technology—it was a critical shortage of problem-solving capabilities among frontline supervisors.

2. Behavioral Pattern Mapping

Next, document how work actually happens vs. how it's supposed to happen:

What behaviors consistently occur despite formal processes?

Which behavioral patterns create excellence vs. problems?

How do behaviors spread through the organization?

Where do individual behaviors conflict with system needs?

A fastener distributor used this approach to discover that their "maverick" warehouse lead, often viewed as difficult, had actually developed highly effective workarounds for flawed processes. Rather than forcing compliance, they formalized and spread his innovations.

3. Incentive Structure Review

Examine what behaviors are actually being rewarded vs. what you want to encourage:

What formal incentives exist across the organization?

What informal rewards and recognition systems operate?

How do social dynamics create incentives or disincentives?

Where do incentives conflict with desired outcomes?

An industrial supplies distributor realized their sales incentive structure was creating severe operational problems through end-of-month order surges. By restructuring incentives to reward even ordering patterns, they improved operational efficiency by 23% with no additional resources.

4. Communication Pattern Analysis

Finally, map how information actually flows through your organization:

Who communicates with whom about what topics?

Where does information get stuck, distorted, or lost?

How do departmental boundaries affect communication?

What communication technologies help or hinder understanding?

A medical supplies distributor applied this analysis and discovered that their chronically poor fill rate stemmed not from inventory issues but from communication barriers between customer service and purchasing. By implementing structured communication protocols, they improved fill rates by 7% without increasing inventory.

Implementation: Bringing Human Elements to Life

Understanding human elements is only valuable if it leads to implemented improvements. Based on my experience with dozens of distributors, I've found four principles critical for successful human element implementation:

1. Co-creation Rather Than Imposition

Human systems resist change that feels imposed from outside. Instead:

Involve those affected in designing the changes

Create opportunities for people to shape implementation

Build on existing behavioral patterns where possible

Frame changes as extensions of current values rather than rejections

A building products distributor involved their warehouse team in redesigning their picking process. The resulting system not only performed better technically but was implemented in half the expected time due to natural workforce buy-in.

2. Progressive Implementation

Unlike physical or technological changes that can be implemented all at once, human elements typically require gradual evolution:

Start with small, visible wins that build confidence

Sequence changes to build on each other

Allow time for new behavioral patterns to stabilize

Use early adopters to demonstrate and champion changes

An electrical distributor implemented their new communication protocols one department at a time, using each successful implementation as a case study for the next group. This approach reduced resistance and accelerated adoption.

3. Continuous Feedback Loops

Human systems adapt and evolve constantly, requiring ongoing adjustment:

Create regular checkpoints to assess implementation

Develop clear signals that indicate success or struggle

Build in mechanisms for easy course correction

Celebrate and publicize successful adaptation

A plumbing distributor implemented weekly "human element huddles" where teams could raise issues with new systems and suggest improvements. This feedback mechanism allowed them to rapidly iterate their implementation, addressing issues before they became obstacles.

4. Psychological Safety

Perhaps most importantly, human element changes require psychological safety—the belief that one can speak up, experiment, and even fail without facing punishment or humiliation:

Explicitly separate learning from evaluation

Model vulnerability and openness to feedback

Recognize effort and learning, not just outcomes

Address blame-oriented language and behavior directly

An HVAC distributor transformed their error reporting process from a punitive system to a learning-oriented one. Within six months, reported errors increased by 300% (revealing previously hidden issues), while actual error rates decreased by 60% due to better system learning.

Connecting Human Elements to Other Operational Elements

Human elements don't exist in isolation. They interconnect with the other fundamental elements of your operation:

Physical Elements: Humans interact with physical infrastructure and equipment

Process Elements: Humans execute, adapt, and sometimes circumvent processes

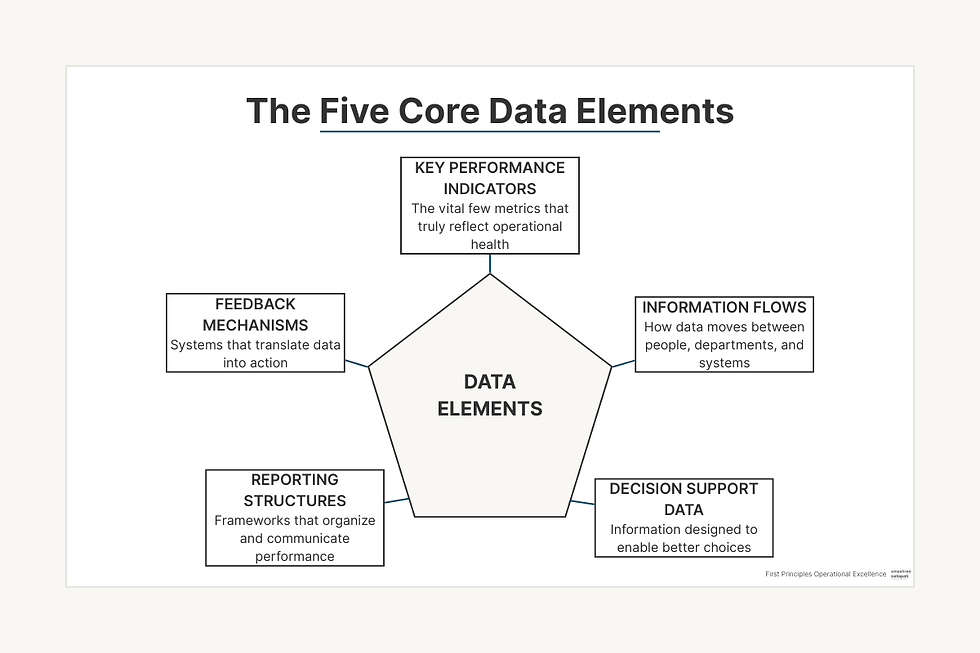

Data Elements: Humans both generate and consume data

Financial Elements: Human behavior ultimately drives financial outcomes

The most successful distributors recognize these connections and design human elements that create harmony rather than friction across their operations.

Taking Action: Your Next Steps

If you're ready to start addressing the human elements in your operation, here are four concrete next steps:

Select a specific operational challenge that you suspect has human element dimensions. Order accuracy, inventory discrepancies, and cross-departmental friction are often good starting points.

Map the four human elements (skills, behaviors, incentives, and communication) that relate to this challenge, focusing on what actually happens rather than what should happen.

Identify one high-leverage intervention that could address a critical human element gap, prioritizing changes that work with rather than against human psychology.

Implement using co-creation, involving those who will be affected in designing the specific implementation approach.

Remember, the goal isn't to create perfect human systems immediately. Instead, focus on making incremental improvements that harness rather than fight the complex psychology of your operational teams.

Building Your Human Element Mastery

Understanding and optimizing human elements isn't a one-time project but an ongoing capability. As you develop this capability, you'll find that previously intractable operational challenges become increasingly solvable.

The plumbing distributor I mentioned earlier ultimately transformed their relationship with human elements, creating systems that worked with rather than against human psychology. Three years later, their CEO told me: "We used to think we had technology and process problems. Now we understand that most of our challenges were human element issues in disguise. Once we learned to see and design for these elements, everything else became easier."

By breaking down your operations to these fundamental human elements, you gain the ability to rebuild with intention and purpose. And in today's competitive distribution landscape, this capability may be your most sustainable advantage.

What human element challenges do you face in your distribution operation? Have you experienced the myth of the rational operator in your systems? I'd love to hear your thoughts in the comments below.

Want a structured approach to analyzing and optimizing the human elements in your distribution operation? Drop a message using the contact form to get the Free Human Elements Assessment Framework.

Comments